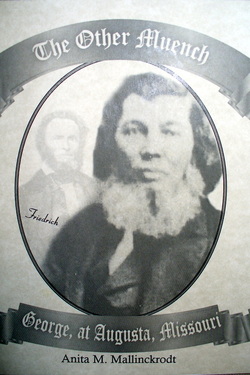

The Other Muench by Anita M. Mallinckrodt

The Other Muench: George, At Augusta, Missouri

Copyright 2012 Anita M. Mallinckrodt, Ph.D.

ISBN 0-931227-20-8

To obtain the book, contact:

Anita Mallinckrodt

Haus Dortmund

498 Schell Road

Augusta, MO 63332

636-228-4821

February 26, 2013

THINGS I DIDN’T KNOW ABOUT GEORG MUENCH… A REVIEW OF THE OTHER MUENCH

By James F. Muench

My wife told me once that I look more like Georg than Friedrich. I just laughed that off. I have always felt a greater kinship with my ancestor, Friedrich Muench, because he was a writer too. I never really thought about Georg. In my mind, he was more or less Friedrich’s sidekick.

But reading Anita Mallinckrodt’s new book, The Other Muench: George, at Augusta, Missouri, taught me that the character of Georg Muench was much more complex. I learned quite a few intriguing facts about Georg, Friedrich's brother and partner in good works, and I now feel a much greater kinship with him as well as his brother.

For instance, one thing that struck me was that George is said to have had a great voice, a fact I had not known before. I too love to sing. There’s a little music in all Muenches, but finding another singer in the bunch was a priceless gift.

It was also interesting that the Muench brothers were both ordained Lutheran ministers. Georg replaced Friedrich as pastor of the church in Niedergemuenden when his brother immigrated to Missouri. Likewise, their younger brother, Ludwig, followed a similar path to the ministry and Missouri.

And Friedrich and Georg both earned theology degrees from the University of Giessen. More importantly, they were inculcated there in the philosophy of the Enlightenment, an era marked by a package of universal ideas originally spawned in France and given expression in Britain and other European countries that aimed to improve the lot of humanity. Although I had known they were educated thinkers, I had never made the connection with the Enlightenment as Mallinckrodt has done in her book.

It makes sense. The Enlightenment was more than an era; it was a philosophical movement, which taught that educated people using secular, rational thought would lead to the reform and improvement of civilization. It’s basically what we often think of as the American faith in progress, often personified by Ben Franklin, the Wright Brothers and Thomas Edison. As the United States became the unparalleled political expression of Enlightenment thought, it was only natural that the Muench brothers would choose to emigrate here eventually as life in the home country grew more reactionary.

According to Mallinckrodt, rationalism or “free thinking,” a related movement within the study of theology, also shaped the Muench brothers’ actions as they helped to forge a better society in the New World. Rationalism valued humanistic reason and universal human ideals over mystical church dogma, and it may partly explain why the Muench brothers, although ordained pastors and still professed Christians, did not make the work of the church the primary focus of their lives upon their move to America.

That strain of rationalist thought remains strong in the Muench family today. My grandfather, Albert F. Muench, held agnostic beliefs and did not believe in organized religion. Although my father, Laurence W. Muench, disagreed with granddad and adhered to the Christian faith, he too held firm to humanistic principles and often dismissed what he called “mysticism.” Likewise, although I am a Presbyterian carrying on the Reformed tradition, I also often find myself questioning theological dogma in favor of a more rational approach to piety. God wants us to think and question. That’s how we grow spiritually.

Finally, and perhaps most interesting, is the information Mallinckrodt presents about the Muench brothers’ participation in the politics of their time. While I’ve long known something of the political importance the brothers Muench played in the mid-19th Century, between the buildup to the Civil War and the Reconstruction era, Mallinckrodt located some fascinating stories I had not heard before, such as Georg’s participation in an effort to free an escaped slave who had been recaptured in Augusta. Georg led the creation of a 50-man armed posse to rescue and set free a runaway slave who had been recaptured in Augusta.*

Mallinckrodt’s book showed me that Georg was no mere sidekick. He was much more than just a Tonto to the Lone Ranger, a Kato to the Green Hornet, or a Robin to Batman. No, as the more public face of the Missouri Muench partnership, Friedrich may have played the president’s role, but Georg played the role of CEO, the guy who made things happen behind the scenes.

They were a team of partners doing good.

###

*This new text reflects a correction, issued by Anita Mallinckrodt. There is no evidence that Georg was a participant in the formal abolitionist network of slave safe havens known today as "the Underground Railroad." This particular 1863 event was an individual action in which Georg played a major leadership role.

Copyright 2012 Anita M. Mallinckrodt, Ph.D.

ISBN 0-931227-20-8

To obtain the book, contact:

Anita Mallinckrodt

Haus Dortmund

498 Schell Road

Augusta, MO 63332

636-228-4821

February 26, 2013

THINGS I DIDN’T KNOW ABOUT GEORG MUENCH… A REVIEW OF THE OTHER MUENCH

By James F. Muench

My wife told me once that I look more like Georg than Friedrich. I just laughed that off. I have always felt a greater kinship with my ancestor, Friedrich Muench, because he was a writer too. I never really thought about Georg. In my mind, he was more or less Friedrich’s sidekick.

But reading Anita Mallinckrodt’s new book, The Other Muench: George, at Augusta, Missouri, taught me that the character of Georg Muench was much more complex. I learned quite a few intriguing facts about Georg, Friedrich's brother and partner in good works, and I now feel a much greater kinship with him as well as his brother.

For instance, one thing that struck me was that George is said to have had a great voice, a fact I had not known before. I too love to sing. There’s a little music in all Muenches, but finding another singer in the bunch was a priceless gift.

It was also interesting that the Muench brothers were both ordained Lutheran ministers. Georg replaced Friedrich as pastor of the church in Niedergemuenden when his brother immigrated to Missouri. Likewise, their younger brother, Ludwig, followed a similar path to the ministry and Missouri.

And Friedrich and Georg both earned theology degrees from the University of Giessen. More importantly, they were inculcated there in the philosophy of the Enlightenment, an era marked by a package of universal ideas originally spawned in France and given expression in Britain and other European countries that aimed to improve the lot of humanity. Although I had known they were educated thinkers, I had never made the connection with the Enlightenment as Mallinckrodt has done in her book.

It makes sense. The Enlightenment was more than an era; it was a philosophical movement, which taught that educated people using secular, rational thought would lead to the reform and improvement of civilization. It’s basically what we often think of as the American faith in progress, often personified by Ben Franklin, the Wright Brothers and Thomas Edison. As the United States became the unparalleled political expression of Enlightenment thought, it was only natural that the Muench brothers would choose to emigrate here eventually as life in the home country grew more reactionary.

According to Mallinckrodt, rationalism or “free thinking,” a related movement within the study of theology, also shaped the Muench brothers’ actions as they helped to forge a better society in the New World. Rationalism valued humanistic reason and universal human ideals over mystical church dogma, and it may partly explain why the Muench brothers, although ordained pastors and still professed Christians, did not make the work of the church the primary focus of their lives upon their move to America.

That strain of rationalist thought remains strong in the Muench family today. My grandfather, Albert F. Muench, held agnostic beliefs and did not believe in organized religion. Although my father, Laurence W. Muench, disagreed with granddad and adhered to the Christian faith, he too held firm to humanistic principles and often dismissed what he called “mysticism.” Likewise, although I am a Presbyterian carrying on the Reformed tradition, I also often find myself questioning theological dogma in favor of a more rational approach to piety. God wants us to think and question. That’s how we grow spiritually.

Finally, and perhaps most interesting, is the information Mallinckrodt presents about the Muench brothers’ participation in the politics of their time. While I’ve long known something of the political importance the brothers Muench played in the mid-19th Century, between the buildup to the Civil War and the Reconstruction era, Mallinckrodt located some fascinating stories I had not heard before, such as Georg’s participation in an effort to free an escaped slave who had been recaptured in Augusta. Georg led the creation of a 50-man armed posse to rescue and set free a runaway slave who had been recaptured in Augusta.*

Mallinckrodt’s book showed me that Georg was no mere sidekick. He was much more than just a Tonto to the Lone Ranger, a Kato to the Green Hornet, or a Robin to Batman. No, as the more public face of the Missouri Muench partnership, Friedrich may have played the president’s role, but Georg played the role of CEO, the guy who made things happen behind the scenes.

They were a team of partners doing good.

###

*This new text reflects a correction, issued by Anita Mallinckrodt. There is no evidence that Georg was a participant in the formal abolitionist network of slave safe havens known today as "the Underground Railroad." This particular 1863 event was an individual action in which Georg played a major leadership role.